The question “are Mexicans native American” sparks heated debates across academic circles, indigenous communities, and policy discussions. This complex identity question touches the very heart of how we define indigeneity in North America. The answer isn’t simple—it depends on genetics, culture, politics, and personal identity.

The Genetic Foundation: What Science Reveals About Mexican People

Recent groundbreaking genetic research paints a fascinating picture of Mexican ancestry. Large-scale mitochondrial sequencing studies reveal that 85 to 90% of maternal lineages in Mexican people trace back to Native American origins. This means the vast majority of Mexican people carry indigenous genetic markers passed down through thousands of generations.

Modern genetic analysis shows something remarkable. Scientists studying over 1,000 individuals representing 20 indigenous and 11 mestizo populations found striking genetic stratification among indigenous populations within Mexico—some groups as differentiated as Europeans are from East Asians. This diversity reflects the rich pre-Columbian heritage that predates European contact by millennia.

The genetic data tells us that most Mexican people are primarily indigenous. Studies consistently show that Mexicans who self-identify as Mestizos are primarily of European and Native American ancestry, with the largest genetic component being indigenous. Even those who don’t identify culturally as indigenous often carry substantial native Mexican genetic heritage.

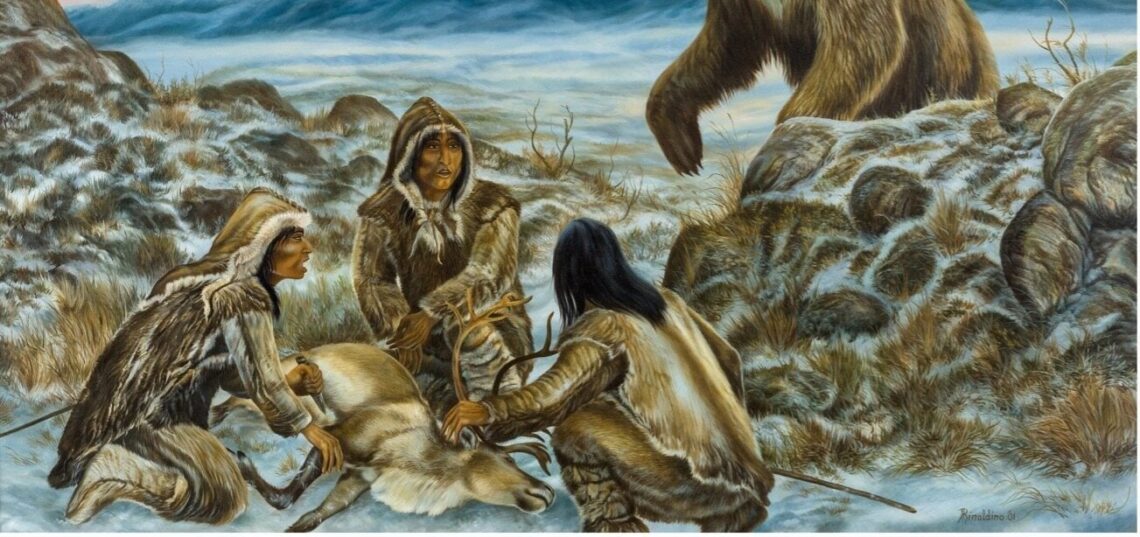

Ancient Migrations: From Siberian Origins to the Bering Strait

Understanding whether Mexicans are native American requires examining deep ancestral connections. Indigenous Mexicans originated from a lineage that diverged from Ancient East Asians around 36,000 years ago and subsequently merged with a Paleolithic Siberian population. This ancestral population eventually crossed the Bering Strait during the last Ice Age.

The Clovis people, long considered among the earliest inhabitants of North America, provide crucial evidence. Archaeological sites show that Clovis culture extended from southern Canada to northern Mexico and across the continent. Genetic analysis of the famous Anzick-1 Clovis child reveals direct connections to modern indigenous peoples, particularly those from Central and South America.

Multiple migration waves shaped the genetic landscape. Evidence suggests at least four distinct streams of migration from Asia, beginning as early as 23,000 years ago. These ancient peoples didn’t recognize modern political borders—they moved freely across what we now call Mexico, the United States, and Canada.

Research on ancient DNA shows that all people studied were descended from migrants who crossed the Bering Strait into North America more than 15,000 years ago. This shared heritage connects Mexican indigenous populations directly to the broader Native American family tree.

The Complexity of Indigenous Mexican Identity

Determining if a Mexican person is native American involves more than genetics. Mexico recognizes 68 distinct indigenous groups, each with unique languages, traditions, and cultural practices. The Mexican census defines Indigenous Mexicans through cultural-ethnicity of communities that preserve their Indigenous languages, traditions, beliefs, and cultures.

This cultural definition creates complexity. Many Mexican people have substantial indigenous ancestry but don’t maintain traditional languages or customs. Others actively identify with specific indigenous nations like the Zapotec, Mixtec, or Maya peoples. The question “is Mexican a race” misses the point—it’s about cultural connection and community belonging.

Some indigenous Mexican communities maintain strong ties to their ancestral heritage. In California alone, 200,000 people are descended from one or more of Mexico’s over 60 Indigenous groups, with 100,000 to 150,000 Indigenous Oaxacans calling the state home. These communities often identify as both Mexican and Indigenous.

The reality is that “is Mexican an ethnicity” depends on individual circumstances. A person might be genetically indigenous, culturally Mexican, and politically excluded from tribal recognition. This creates unique challenges for Mexican people seeking to understand their native American heritage.

Physical Characteristics and Ancestral Connections

Many Mexican people display physical traits that reflect their indigenous heritage. Features like epicanthic folds—the skin fold covering the inner corner of the eye—connect Mexican populations to their Asian ancestors who crossed the Bering Strait. Some Mexican people look Asian because they share common ancestral origins with East Asian populations.

These physical characteristics aren’t universal among Mexican people due to centuries of mixing with European and African populations. However, they provide visible evidence of the deep indigenous roots that genetic studies confirm. The diversity in appearance among Mexican people reflects the complex history of population mixing in North America.

Understanding these connections helps answer whether native Mexican identity fits within broader definitions of Native American heritage. The shared ancestral journey from Asia through the Bering Strait created genetic and cultural links that transcend modern national boundaries.

Political Recognition and Legal Realities

The question of whether Mexicans are considered native Americans becomes complicated when examining legal and political recognition. In the United States, tribal membership typically requires documented genealogical connection to federally recognized tribes. Most Mexican people, despite substantial indigenous ancestry, don’t meet these specific requirements.

This creates a paradox. A person might be genetically more indigenous than someone with tribal membership, yet receive no legal recognition as Native American. The political history of conquest, colonization, and border changes separated many indigenous Mexican families from their tribal connections.

Some indigenous Mexican communities span both sides of the modern US-Mexico border. The Tohono O’odham people, for example, have tribal lands in both Arizona and Sonora. These communities challenge simple definitions of Mexican versus Native American identity.

Federal recognition systems often exclude indigenous Mexican people who maintain cultural traditions but lack specific tribal affiliation documents. This bureaucratic barrier doesn’t erase their indigenous heritage—it simply reflects political boundaries that didn’t exist when their ancestors first inhabited these lands.

Cultural Preservation and Modern Identity

Indigenous Mexican communities actively preserve their ancestral traditions while navigating modern identity questions. Whether someone identifies as native Mexican, indigenous Mexican, or simply Mexican often depends on their connection to specific cultural practices and community networks.

Language preservation plays a crucial role. Mexico recognizes 68 indigenous languages as national languages, reflecting the country’s commitment to maintaining pre-Columbian cultural heritage. Speakers of these languages often have stronger claims to indigenous identity than those who’ve adopted Spanish as their primary language.

Traditional knowledge systems, spiritual practices, and land relationships also define indigenous Mexican identity. Many communities maintain agricultural techniques, medicinal knowledge, and ceremonial practices that date back thousands of years. These cultural connections matter as much as genetic heritage in determining indigenous identity.

The Chicano movement of the 1960s and 1970s helped many Mexican Americans reconnect with their indigenous roots. Chicanos began to embrace their native heritage, leading to protests and civil rights movements that gained exposure for Mexican American identity. This cultural awakening highlighted the indigenous foundations of Mexican identity.

Looking Forward: Reclaiming Indigenous Heritage

The evidence overwhelmingly supports the indigenous heritage of Mexican people. Genetic studies confirm that most Mexican people carry substantial native American ancestry. Cultural practices and languages maintain connections to pre-Columbian traditions. Archaeological evidence shows continuous indigenous presence in Mexico for thousands of years.

The real question isn’t whether Mexican people have native American heritage—it’s how they choose to express and honor that heritage. Some embrace specific tribal identities. Others identify more broadly as indigenous. Many simply acknowledge their mixed heritage while focusing on Mexican national identity.

Understanding this complexity helps bridge divides between different indigenous communities in North America. Rather than asking “are Mexicans considered native Americans,” we might ask how to support all indigenous peoples in maintaining their cultural heritage and political rights.

The genetic evidence is clear: Mexican people are largely indigenous to North America. Their ancestors crossed the Bering Strait, developed complex civilizations, and maintained continuous presence for millennia. Political borders and colonial classifications don’t erase this fundamental truth.

This shared heritage creates opportunities for solidarity between indigenous Mexican communities and other Native American groups. By recognizing these connections, we can work toward more inclusive definitions of indigenous identity that honor both cultural specificity and ancestral unity across North America.